Understanding Dehydration

the CliffsNotes

Home working has marked a loss of ‘water cooler chat’ for many. Although the focus is often on the social aspect of this change, the loss of a regular prompt to drink water is just as significant. At FCLabs, we want to make sure our team is operating at their best- and that requires being properly hydrated. The added benefit is improvements in short and long-term health outcomes. Win-win!

The blog is below. If you want to dig deeper, the full paper with references is available here:

Let’s dive in.

What this issue covers

What is dehydration - how complicated can the loss of water be?

The effects of dehydration

The links between dehydration and fatigue

How to recognise and prevent dehydration

What is dehydration?

A drop in the amount of water in the body to a level that it can’t function to the best of its ability.

A drop of just 2% can cause a decline in function.

There are different types of dehydration, depending on whether the loss of water occurs inside or outside cells, leading to differences in whether it’s just water that is lost or vital nutrients that the body needs to function.

For much of the 20th century, dehydration brought on by severe illness (we’re talking about the kind of processes associated with food poisoning…) was most studied. Why? Because that is the kind of dehydration that most often leads to hospitalisation.

However, an increasing understanding of the water needs of the body is leading to an understanding of the dangers of the simplest form of dehydration: that brought on by a lack of fluid intake.

Despite 74% of the world’s population having access to clean drinking water, many are ‘low drinkers’, causing their body to work at conserving water as it thinks there isn’t enough available.

There are short and long-term negative effects to this - and with better drinking habits it’s a solvable problem.

What does dehydration do to us?

let’s get past the obvious ones: dehydration causes thirst and decreases sweating and this leads to a reduction in the ability of the body to regulate its temperature.

This is because the body is attempting to save water. Dehydration causes additional amounts of a hormone to be released that in turn makes the kidneys work overtime to put water back into the bloodstream rather than let it flow out of the body.

Frequent and prolonged dehydration can cause long-term problems for the kidneys. In the shorter term, dehydration causes a decline in physical abilities, particularly endurance.

Surprisingly, up to a certain level, dehydration doesn’t affect cognitive abilities significantly. This is because the brain recognises that it needs to work harder to achieve the same outcome - and prioritises that. So, when dehydrated, the part of your brain that is used to make important decisions will get more attention than other parts of the body: strength is sacrificed to maintain the ability to make the right decisions.

This is called cognitive flexibility and allows for normal cognitive abilities in mild cases of many maladies. The problem with this impressive ability is that it masks deficiencies (such as dehydration) that can then lead to other health complications.

Dehydration and fatigue

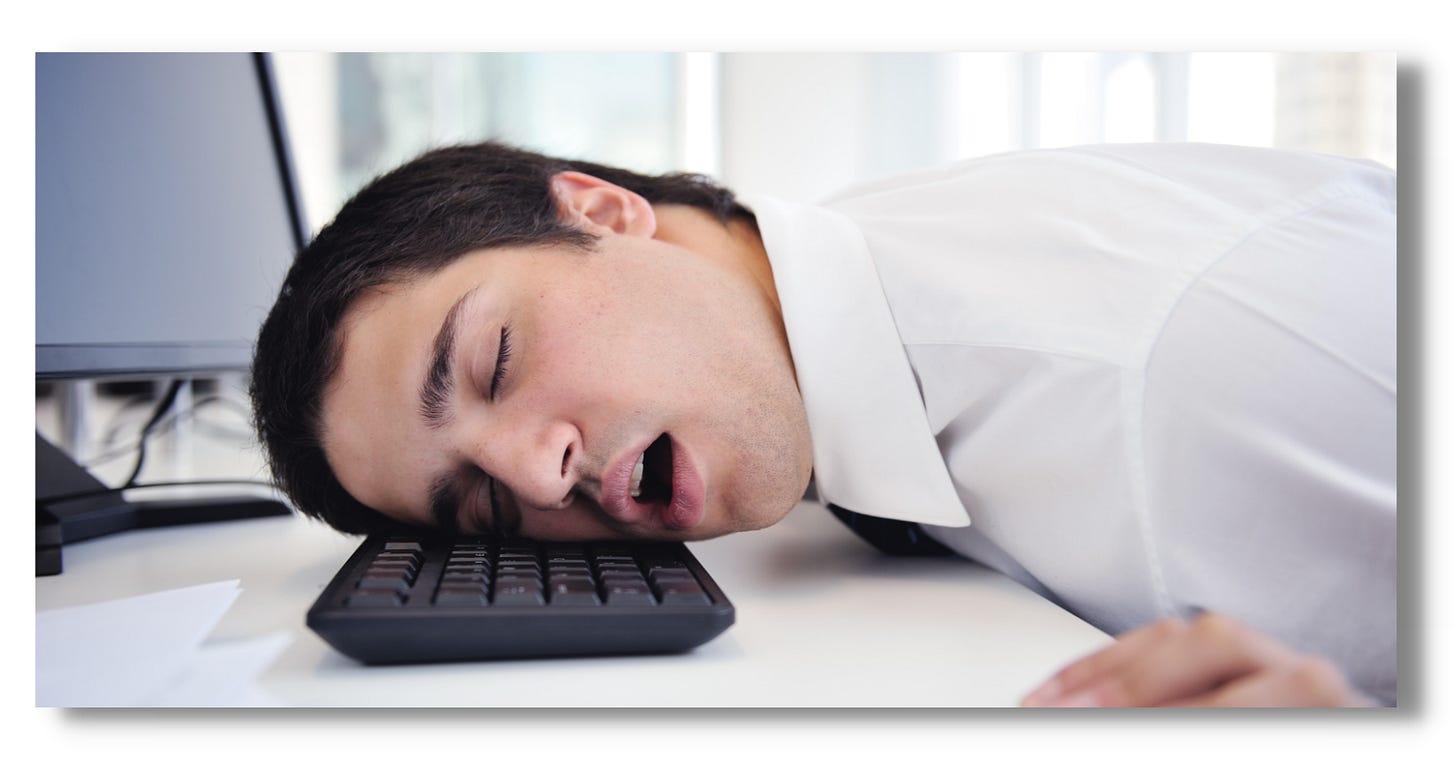

It’s all fine and well having the same abilities to perform cognitive tasks if dehydrated - unless a person isn’t willing to take that decision in the first place.

Dehydration leads to the earlier onset of fatigue. This means someone running a marathon will want to stop earlier if dehydrated; productivity at work will rapidly decline after 3 hours rather than 4; running around the park with the kids or grandkids will seem too much of an effort compared to sitting on the couch.

The odd thing about fatigue is that, at the level that most experience it, it’s all in the mind. Studies consistently show that when someone feels they ‘can’t go on’, there is no physical reason for it. There seems to be a built-in mechanism to leave something in the tank.

Workers carrying out physical jobs will subconsciously break for around 7 minutes per hour.

However, in poor conditions with a lack of hydration, this can increase to 28 minutes per hour. A poor environment for the worker and a lack of productivity for the employer. Bring back the water cooler!

Footballers also exhibit this self-regulation- and it pays off. Many players, after periods of extreme activity, balance this out with lower-than-average activity. This ensures less dehydration and less fatigue. Players who successfully do this contribute more to the second half of football games. A team where the majority of football players can do this will beat a team with more skill who can’t do this.

This subconscious self-regulation is also seen when preparing for exertion. People who are warned about upcoming physical activity will perform better than those who are not. By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail (thanks, Postmaster General B. Franklin)- and that goes for the body as well.

Combating dehydration

Recognise it

Humans are likely to be dehydrated if they lose more than 2% of their body mass. That’s not much - it’s hard to notice when 2% of something is missing.

Dehydration can be most accurately tested through blood tests - also saliva, tear and urine testing. Heart rate has also been shown to vary significantly when someone is dehydrated.

But these tests aren’t too practical for the general population. So, it’s back to basics: recognising when urine is a darker colour, when it is of reduced volume, or when thirst develops - and then making sure to take the prompt and drink some water.

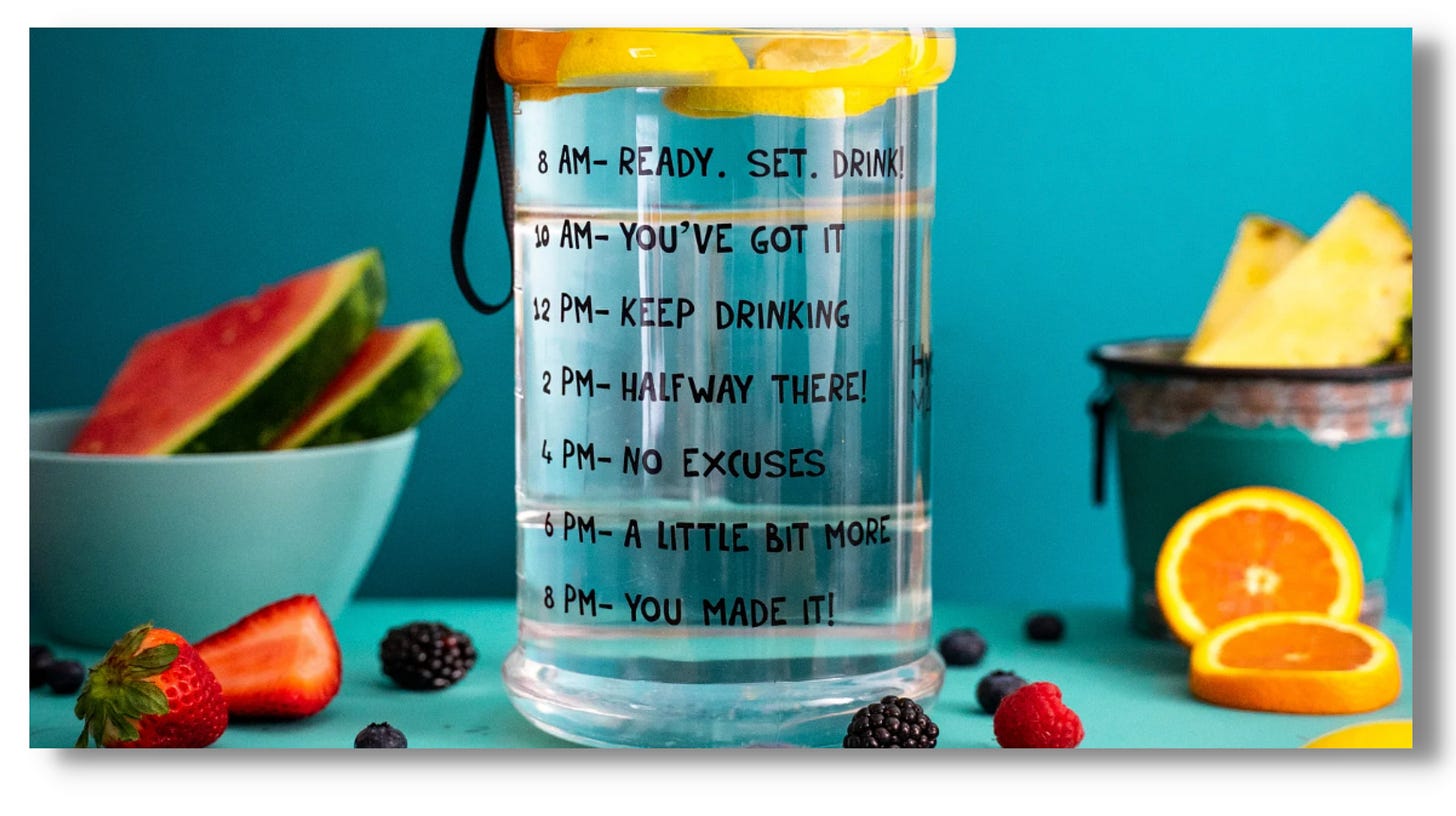

But, the best idea is to:

Stay hydrated

In the early 20th century, Lawrence of Arabia had his fighters consume copious amounts of water before a fight in an effort to prevent them from dehydrating. The idea was right - wouldn’t want fatigue to play a part halfway through the fight - but unfortunately we now know that the science doesn’t add up (and it could actually do more harm than good).

Despite the body being made of between 45 and 75% water (this depends on age, sex and fat volume), it’s poor at storing water for future use. No camels here.

The human body needs a balance of water to function. This means that regular water intake will always trump a large intake at one time.

How much?

That’s the tricky question. A person can also drink too much water. This results in too small a concentration of salt in the body (hyponatremia). Much of the current guidance is to listen to the body - when someone feels thirsty, they should hydrate.

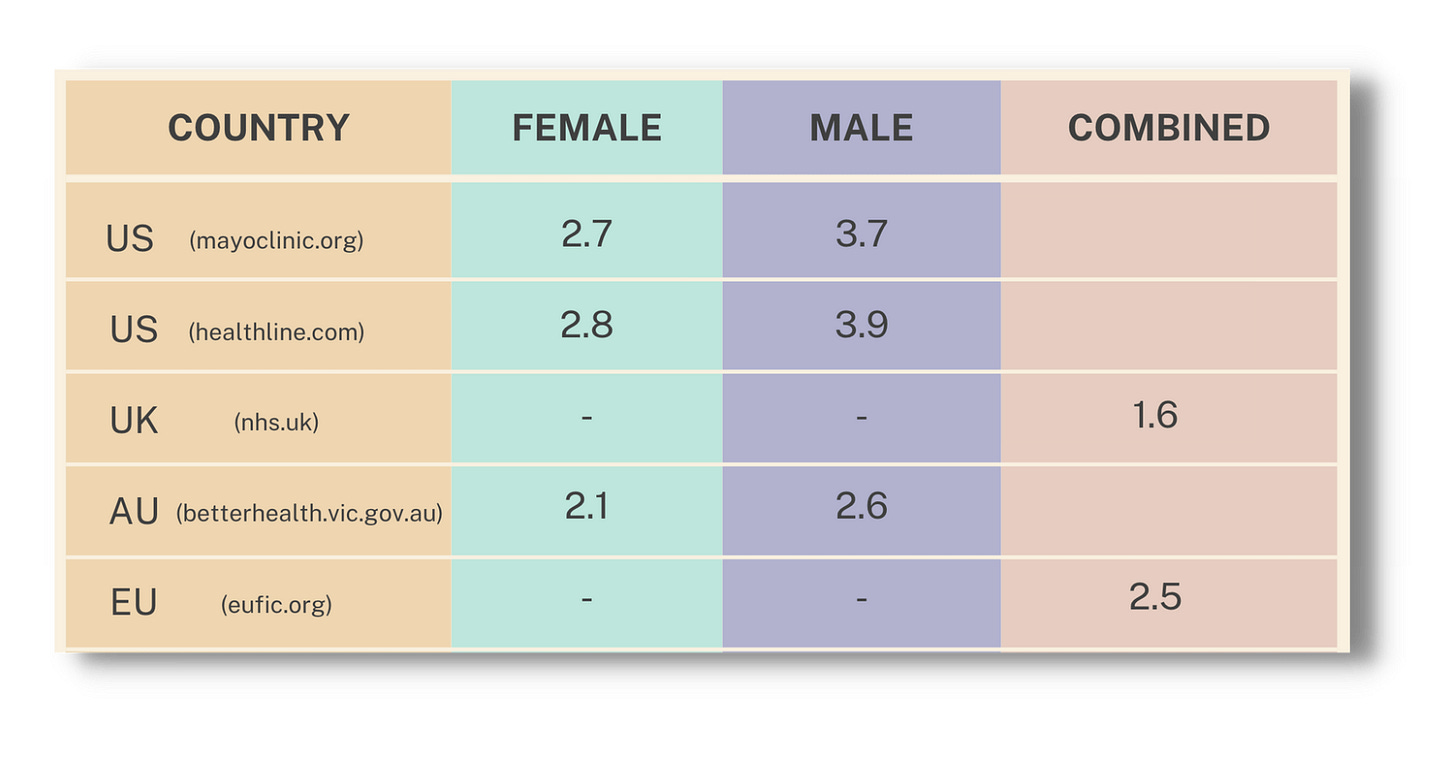

It’s a tough balance, as shown by various guidelines from different countries:

It’s understood now that different people have different water needs, and these also change depending on what activities are undertaken and the age of the person.

We do know that:

feeling thirsty is a sign that someone is dehydrated.

dark and/or low volume of urine is a sign that someone is dehydrated.

Therefore, frequently presenting symptoms such as these may indicate that average water intake should increase, whereas a lack of these symptoms may indicate that average water intake can be allowed to decline slightly.

What’s the takeaway?

A lack of water intake can affect endurance and other physical abilities long before it becomes obvious. It can cause short-term lethargy and endurance problems and long-term health issues.

While cognitive abilities aren’t immediately affected, fatigue is brought on by dehydration so there is a lack of motivation to make decisions in the first place.

People are most at risk of both dehydration and over-hydration when water balance significantly changes from normal. Just as drinking no water for prolonged periods should be avoided, drinking large quantities in a small period of time should be as well. Both instances put additional stress on the kidneys as it attempts to reach an appropriate fluid balance in the body again.

Therefore, habits should be formed that maintain balanced levels of hydration over time. We’ve got some info on successful habit forming in a previous post on wearables and it’s a topic we’ll be delving into more in upcoming posts.

We hope you’ve enjoyed reading NeuroNotes. If you would like a future NeuroNotes to investigate a topic you would like to know more about, feel free to get in touch:

andy@fclabs.co.uk

If you want to dig deeper, the full paper with references is available here: